UTIs and E. coli: From Symptoms & Prevention to Fatal Sepsis

- October 30, 2025

- 1 Like

- 321 Views

- 0 Comments

Section 1: Introduction: The Deceptive Simplicity of Urinary Tract Infections

Urinary tract infections (UTIs) represent one of the most common bacterial infections encountered in clinical practice worldwide, constituting a significant public health issue.1 Each year, they account for millions of ambulatory care visits and are a leading reason for antibiotic prescriptions.2 The majority of these infections are classified as uncomplicated, affecting the lower urinary tract and resolving quickly with a short course of antibiotics, leading to a perception of UTIs as a mere nuisance.4 This perception, however, masks a serious and potentially lethal reality.

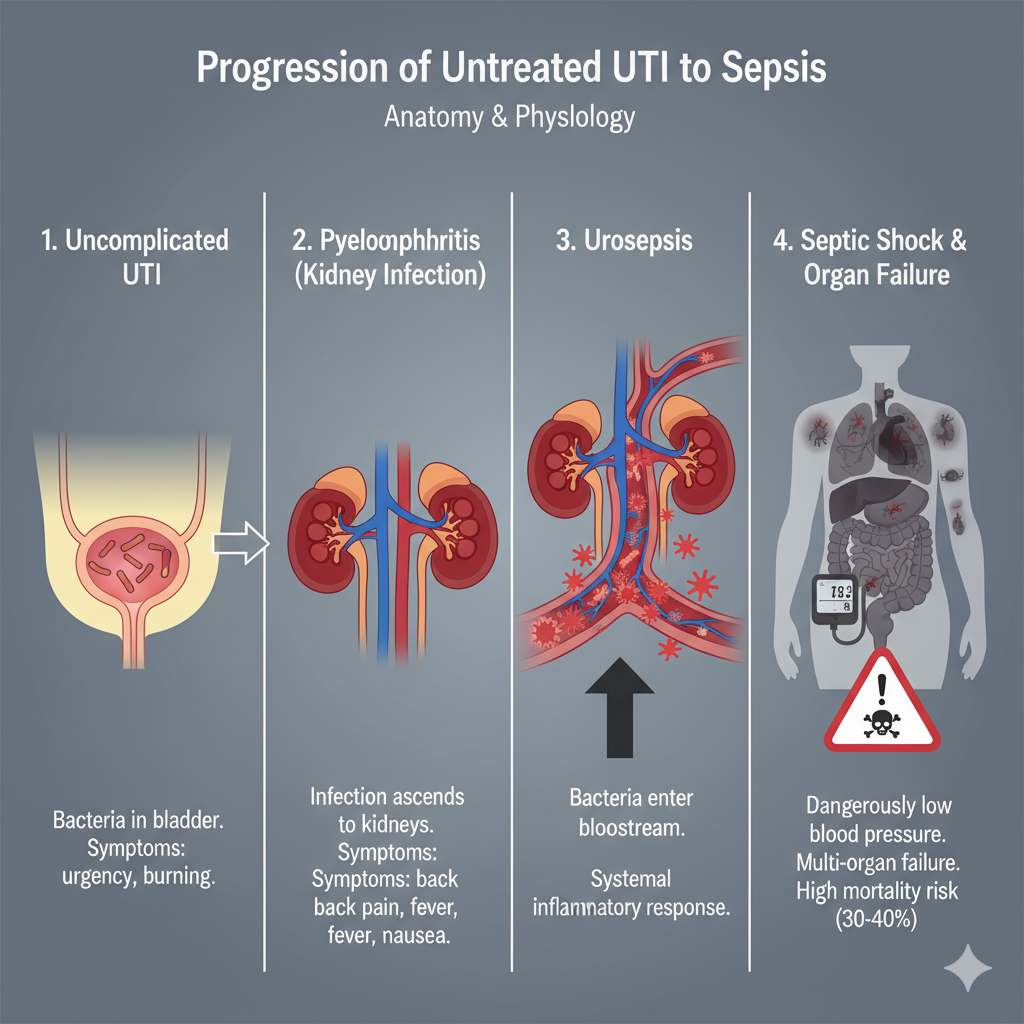

While most UTIs are indeed benign, a subset of these infections, if left untreated, misdiagnosed, or occurring in a vulnerable individual, can initiate a devastating physiological cascade. The infection can ascend from the bladder to the kidneys, breach the body’s local defenses, and seed the bloodstream with bacteria. This event triggers a dysregulated, systemic inflammatory response known as sepsis, which can rapidly progress to septic shock, multi-organ failure, and ultimately, death.4 Understanding this progression is critical, as the mortality rate associated with septic shock can be as high as 30-40%.8

This report provides a comprehensive analysis of urinary tract infections, moving beyond the common ailment to explore the full spectrum of the disease. It will detail the microbial genesis of infection, with a focus on the primary pathogen, Escherichia coli. It will then provide a critical guide to recognizing the early warning signs that distinguish a simple bladder infection from a medical emergency. The core of this analysis will be a detailed examination of the pathophysiological cascade from a localized kidney infection to fatal sepsis. Finally, the report will identify key risk factors that increase vulnerability to severe outcomes and present an evidence-based framework for both symptom management and proactive prevention. The objective is to replace generalized concern with a structured, actionable understanding of how to mitigate the risks of this deceptively simple infection.

Section 2: The Genesis of Infection: Understanding UTIs and the Role of Escherichia coli

2.1 Anatomy of the Urinary Tract: A Sterile Environment Under Siege

The human urinary system is a meticulously designed apparatus for filtering waste from the blood and expelling it from the body. It consists of four primary components: the kidneys, which produce urine by filtering blood; the ureters, which are tubes that carry urine from the kidneys to the bladder; the bladder, a muscular sac that stores urine; and the urethra, the tube through which urine exits the body.2 Under normal physiological conditions, the entire urinary tract, with the exception of the distal urethra, is a sterile environment. The urine it contains is composed of fluids, salts, and waste products but is free of bacteria, viruses, or fungi.2 A UTI is, by definition, an invasion and colonization of this sterile space by pathogenic microorganisms.2

A key anatomical feature that heavily influences UTI epidemiology is the difference in urethral length between sexes. In women, the urethra is significantly shorter and is located in close proximity to the anus, the primary reservoir for fecal bacteria. This anatomical arrangement provides a much shorter and more direct path for bacteria to travel from the perineal region into the bladder, which is a principal reason for the higher incidence of UTIs in women.10 Nearly one in three women will experience a UTI requiring treatment by the age of 24.13

2.2 Classifying the Invasion: From Local Irritation to Systemic Threat

UTIs are classified based on their anatomical location, a distinction that is paramount to understanding their clinical severity.

- Lower UTIs: These infections are confined to the lower portion of the urinary tract. They include urethritis (infection of the urethra) and cystitis (infection of the bladder). Cystitis is the most common form of UTI and is typically what is meant by a “simple” or “uncomplicated” bladder infection.2

- Upper UTIs: This far more serious category involves the upper urinary tract. Pyelonephritis, an infection of the kidney parenchyma and renal pelvis, is the primary form of upper UTI. It almost always results from an untreated lower UTI that has ascended through the ureters.2 Pyelonephritis represents a significant escalation of the infection and is the critical gateway to life-threatening systemic complications.

Clinically, UTIs are also categorized as either uncomplicated or complicated. This classification is essential for risk stratification and treatment decisions.

- Uncomplicated UTIs occur in otherwise healthy, non-pregnant individuals who have no structural or neurological abnormalities of the urinary tract.1

- Complicated UTIs are associated with underlying host factors that compromise the urinary tract or immune defense. These factors include urinary obstruction (e.g., from an enlarged prostate or kidney stone), the presence of an indwelling catheter, immunosuppression, renal failure, or pregnancy.1 Patients with complicated UTIs are at a much higher risk for treatment failure and progression to severe disease.

2.3 The Prime Suspect: Uropathogenic Escherichia coli (UPEC)

While a range of pathogens can cause UTIs, one bacterium is overwhelmingly responsible: Escherichia coli. This single species is the causative agent in approximately 80-90% of all community-acquired UTIs.12 It is important to note that most E. coli strains reside harmlessly as part of the normal gut flora. However, specific strains known as uropathogenic E. coli (UPEC) possess a unique arsenal of virulence factors that enable them to successfully invade and colonize the urinary tract.1

The pathogenesis of a UTI is not a passive event of accidental contamination but an active process of microbial invasion. The process typically begins with the contamination of the periurethral area by UPEC from the gut. From there, the bacteria ascend the urethra and migrate into the bladder.1 Once in the bladder, UPEC must overcome the body’s primary defense mechanism: the flushing action of urination. They achieve this through specialized virulence factors, most notably adhesive organelles called P-fimbriae. These hair-like appendages act like grappling hooks, binding with high affinity to specific receptors on the surface of the uroepithelial cells that line the bladder wall.20 This tenacious adhesion prevents the bacteria from being washed away, allowing them to multiply, establish a colony, and trigger the inflammatory response that causes the symptoms of cystitis. This specialized ability to adhere is a key reason why UPEC is such a dominant uropathogen compared to the myriad of other bacteria present in the gut.

While UPEC is the primary actor, other microorganisms can also cause UTIs, particularly in complicated or hospital-acquired cases. These include Klebsiella pneumoniae, Staphylococcus saprophyticus (common in young, sexually active women), Enterococcus faecalis, and Proteus mirabilis.1

2.4 An Emerging Vector: The Foodborne Pathway of UTIs

Traditionally, the source of UPEC in UTIs has been considered endogenous, originating from the individual’s own gut flora. However, recent and paradigm-shifting research has identified a significant external vector: the food supply. A large-scale, multi-year genomic study revealed that a substantial portion of UTIs may be a foodborne illness.22

The investigation analyzed thousands of E. coli isolates from both UTI patients and retail meat samples (including chicken, turkey, and pork) from the same geographic region. Using advanced genomic attribution modeling, researchers determined that approximately 18% of the E. coli UTIs in the patient population were likely caused by zoonotic strains—that is, strains genetically linked to those found in the contaminated meat.22 This finding suggests a more complex pathway for infection: extraintestinal pathogenic E. coli (ExPEC) can originate in food-producing animals, contaminate meat during processing, be ingested by humans, colonize the human gut, and subsequently cause a UTI. This reframes the prevention of a significant number of UTIs from a matter of purely personal hygiene to a broader public health issue encompassing food safety regulations, agricultural practices, and retail handling standards. The study further highlighted a socioeconomic disparity, finding that individuals living in high-poverty neighborhoods had a significantly increased risk of contracting these zoonotic UTIs, potentially due to differences in food safety oversight and retail conditions.22

Section 3: Recognizing the Threat: Early Warning Signs of Lower and Upper UTIs

The ability to distinguish between the symptoms of a lower UTI and an upper UTI is arguably the most critical piece of knowledge for preventing a fatal outcome. The former is a manageable condition, while the latter is a medical emergency requiring immediate attention.

3.1 Symptoms of Lower UTIs (Cystitis & Urethritis): The Body’s Initial Alarm

When bacteria have successfully colonized the bladder or urethra, the resulting inflammation produces a distinct set of localized symptoms. While uncomfortable, these signs are not typically associated with immediate systemic danger.

- Urinary Changes: The most classic symptoms relate directly to the act of urination. These include a painful or burning sensation during urination (dysuria), a persistent and often sudden urge to urinate (urgency), and the need to urinate more often than usual, even if only small amounts are passed (frequency).2 Many individuals also report a sensation of incomplete bladder emptying.13

- Localized Pain: Discomfort is typically felt in the lower abdomen, specifically above the pubic bone (suprapubic pain) or as a feeling of pelvic pressure.10

- Urine Appearance: The urine itself may change in appearance. It can become cloudy or dark, develop an unusually strong or foul odor, or become tinged with blood (hematuria), which may make it look pink, red, or brown.2

3.2 Red Flag Symptoms of Upper UTIs (Pyelonephritis): The Infection Escalates

The onset of the following symptoms signals a critical escalation. The infection is no longer confined to the bladder but has ascended to the kidneys. These signs are systemic, reflecting a body-wide illness that requires prompt medical intervention to prevent further progression.

- Systemic Signs of Infection: The most prominent red flags are systemic. This includes a high temperature (fever), often above 38°C (100.4°F), which may be accompanied by shaking chills or rigors (uncontrollable shivering).10

- Distinctive Pain: The pain associated with pyelonephritis is characteristically different from that of cystitis. It is typically located in the flank (the side of the body between the ribs and the hip) or the mid-to-lower back, often on one side.2 This is a direct result of inflammation and swelling of the infected kidney.

- Gastrointestinal Distress: Nausea and vomiting are common symptoms of a kidney infection and are part of the systemic response to severe infection.2

- Constitutional Symptoms: A profound sense of being unwell (malaise), extreme fatigue, or weakness is also characteristic.10

3.3 Atypical Presentations: The Masked Danger in Vulnerable Populations

A particularly dangerous aspect of UTIs is their tendency to present with non-classical symptoms in certain vulnerable populations. This can lead to missed or delayed diagnosis, allowing the infection to progress unchecked.

- Older Adults: In the elderly or frail, the classic urinary symptoms may be minimal or absent altogether. Instead, the primary sign of a serious UTI is often a sudden change in mental status. This can manifest as acute confusion, delirium, agitation, unexplained lethargy, or social withdrawal.2 Other signs can include new or worsening urinary incontinence, shivering, or a very low body temperature (below 36°C).10

- Children and Infants: Young children, and especially infants, cannot articulate their symptoms. In this group, a UTI may present with non-specific signs such as a high fever, irritability, poor feeding or loss of appetite, vomiting, or a failure to grow at the expected rate.10 The new onset of bedwetting in a child who was previously toilet-trained can also be a warning sign.10

- Patients with Spinal Cord Injuries or Catheters: Individuals with impaired sensation due to spinal cord injury will not feel the typical pain of a UTI. In this population, signs of infection can include an increase in muscle spasticity, fever, cloudy or foul-smelling urine, or the onset of autonomic dysreflexia—a potentially life-threatening syndrome characterized by a sudden, severe spike in blood pressure.5 For patients with indwelling catheters, fever and pain below the stomach are key indicators.33

| Table 1: Differentiating Lower vs. Upper UTI Symptoms | ||

| Symptom Category | Lower UTI (Cystitis) | Upper UTI (Pyelonephritis) – MEDICAL ATTENTION REQUIRED |

| Pain Location | Lower abdomen, suprapubic area, pelvic pressure 10 | Flank, side, or mid-to-lower back, often one-sided 10 |

| Urination | Burning or pain (dysuria), increased frequency, urgency 2 | May be present, but often overshadowed by systemic symptoms |

| Systemic Signs | Typically absent; may feel generally unwell 26 | High fever (>38°C / 100.4°F), shaking chills, rigors 10 |

| Gastrointestinal | Generally absent | Nausea and vomiting are common 2 |

| General Feeling | Localized discomfort, irritating | Profoundly ill, weak, and fatigued (malaise) 10 |

| Urine Appearance | Cloudy, foul-smelling, possibly blood-tinged 2 | May be cloudy or bloody, but not a primary distinguishing feature |

Section 4: The Cascade to Crisis: How a UTI Can Become Fatal

The journey from a localized bladder infection to a fatal systemic illness follows a well-defined pathophysiological pathway. Each step in this cascade represents a failure of the body’s defenses to contain the infection, leading to progressively more severe and widespread organ damage.

4.1 From Bladder to Kidneys: The Pathophysiology of Pyelonephritis

The critical turning point in the severity of a UTI is the ascent of bacteria from the bladder, up the ureters, and into the kidneys.3 This progression to pyelonephritis can be facilitated by anatomical or functional issues, such as vesicoureteral reflux (VUR), a condition where urine flows backward from the bladder into the ureters, effectively carrying bacteria with it.13 However, it can also occur in an anatomically normal urinary tract if a lower UTI is sufficiently aggressive or goes untreated.

Once bacteria reach the kidneys, they invade the renal parenchyma—the functional tissue responsible for filtration. This invasion triggers a potent and damaging inflammatory response.18 The body’s immune system dispatches large numbers of neutrophils to the site of infection, leading to suppurative inflammation (the formation of pus) and the development of small abscesses within the kidney tissue.18 This intense immunological battle physically damages the delicate structures of the kidneys, including the nephrons, which are the microscopic filtering units.5 In severe or recurrent cases, this process of inflammation and subsequent healing can lead to the formation of scar tissue (fibrosis). This permanent renal scarring can impair the kidney’s ability to function, potentially leading to long-term complications such as chronic kidney disease or secondary hypertension.16

4.2 When Infection Enters the Bloodstream: The Onset of Urosepsis

Urosepsis is defined as sepsis that originates from an infection within the urogenital tract.6 It occurs when the inflammatory process of pyelonephritis damages the kidney tissue to such an extent that the infection is no longer contained. Bacteria breach the compromised blood vessels within the kidney and enter the systemic circulation, a condition known as bacteremia.15

The entry of bacteria into the bloodstream triggers a profound and dangerous shift in the body’s response. The threat is no longer localized; it is systemic. This leads to the clinical syndrome of sepsis. It is crucial to understand that sepsis is not the infection itself, but rather the body’s own dysregulated, overzealous, and ultimately self-destructive response to that widespread infection.6 The immune system, designed to protect the body, begins to cause widespread damage to its own tissues and organs.6 This response is driven by a massive release of inflammatory signaling molecules (cytokines) into the bloodstream. This “cytokine storm” causes systemic inflammation, makes blood vessels leaky (leading to fluid shifting out of the circulation and into tissues), and activates the body’s clotting system in a chaotic manner.8

4.3 Systemic Collapse: Septic Shock and Multi-Organ Failure

The systemic inflammatory response of sepsis can rapidly spiral out of control, leading to a cascade of organ failure. The progression is clinically categorized into stages of increasing severity.

- Severe Sepsis: This stage is defined as sepsis that is accompanied by signs of acute organ dysfunction. This may manifest as an altered mental status (confusion, lethargy), difficulty breathing, or a significant drop in urine output, which is a direct sign of developing kidney injury.8

- Septic Shock: This is the most advanced and life-threatening stage of sepsis. It is clinically defined as severe sepsis with persistent and profound hypotension (dangerously low blood pressure) that does not respond to initial treatment with intravenous fluids.6 This state of refractory hypotension means that blood flow to vital organs is critically impaired (a condition called hypoperfusion), starving them of oxygen and nutrients.36

- Multi-Organ Dysfunction Syndrome (MODS): The state of shock triggers a domino effect of catastrophic organ failure.

- Acute Kidney Injury (AKI): The kidneys, already damaged by the initial infection, are extremely vulnerable to the low blood pressure of septic shock and often fail completely, requiring dialysis.8

- Acute Respiratory Distress Syndrome (ARDS): Widespread inflammation causes the capillaries in the lungs to leak fluid into the air sacs, leading to severe respiratory failure that frequently necessitates mechanical ventilation.8

- Disseminated Intravascular Coagulopathy (DIC): The body’s clotting system becomes dysregulated. Thousands of microscopic blood clots form throughout the body, blocking blood flow to organs and limbs, while simultaneously consuming all available clotting factors, which can lead to uncontrollable bleeding elsewhere.8

- Cardiovascular and Hepatic Failure: The heart muscle can weaken, and the liver can fail due to the combination of poor blood flow and direct inflammatory damage.

This final stage of systemic collapse is what makes a UTI fatal. The mortality rate for patients who progress to septic shock is alarmingly high, estimated to be between 30% and 40%.8 Even for those who survive, recovery is often long, and permanent organ damage, particularly to the kidneys, is common.8

| Table 2: The Clinical Progression of Urosepsis | ||

| Stage of Illness | Clinical Definition | Key Signs & Symptoms |

| Pyelonephritis (Upper UTI) | Infection and inflammation localized to the kidney(s).18 | Fever, chills, flank pain, nausea, vomiting.18 |

| Sepsis | A life-threatening organ dysfunction caused by a dysregulated host response to infection.6 | Fever or low temperature, rapid heart rate, rapid breathing, confirmed or suspected infection.6 |

| Severe Sepsis | Sepsis accompanied by signs of acute organ dysfunction.36 | Sepsis symptoms plus: sudden change in mental status (confusion), difficulty breathing, decreased urine output, abnormal liver function.8 |

| Septic Shock | Severe sepsis with persistent low blood pressure (hypotension) despite fluid resuscitation, leading to inadequate tissue perfusion.9 | Severe sepsis symptoms plus: extremely low blood pressure requiring medication to maintain, weak pulse, rapid heart rate, cold and pale extremities, high blood lactate levels.6 |

Section 5: Identifying Vulnerability: Key Risk Factors for Severe and Recurrent UTIs

Not all individuals are equally at risk of developing a UTI or progressing to severe complications. A confluence of anatomical, behavioral, and medical factors can disrupt the urinary tract’s natural defense mechanisms, creating an environment where infection can take hold and flourish. These risk factors do not merely increase the chance of bacterial exposure; more fundamentally, they represent a failure or bypass of the body’s protective barriers—be they mechanical, anatomical, or microbiological.

5.1 Anatomical and Physiological Factors

- Female Anatomy: As previously noted, the shorter female urethra is a primary, non-modifiable risk factor for UTIs.10

- Post-Menopause: The decline in estrogen levels after menopause causes significant changes in the urogenital tract. The vaginal and urethral tissues become thinner and drier (atrophic vaginitis), and the vaginal pH rises. This disrupts the healthy vaginal microbiome, leading to a decrease in protective Lactobacillus bacteria and allowing for the overgrowth of uropathogens like E. coli.13 Additionally, age-related weakening of pelvic floor muscles can lead to incomplete bladder emptying, leaving a residual pool of urine in which bacteria can multiply.27

- Pregnancy: A combination of hormonal changes that relax the ureters and physical compression of the urinary tract by the growing uterus can impede the normal flow of urine. This urinary stasis increases the risk of infection, and UTIs during pregnancy are more likely to ascend to the kidneys, posing risks to both the parent and the fetus.13

- Structural Abnormalities: Any condition that obstructs or alters the normal flow of urine dramatically increases UTI risk by creating stasis. Common examples include an enlarged prostate (benign prostatic hyperplasia) in men, kidney stones, tumors, urethral strictures, or congenital defects like vesicoureteral reflux (VUR).3 These conditions disrupt the critical mechanical defense of flushing bacteria out of the system.

5.2 Behavioral and Lifestyle Factors

- Sexual Activity: Sexual intercourse is one of the strongest predictors of recurrent UTIs in women. The mechanical action can introduce bacteria from the perineal area into the urethra.14 The risk increases with the frequency of intercourse and with a new sexual partner.39

- Contraception Methods: The use of spermicides, either on condoms or with a diaphragm, is a significant risk factor. Spermicides disrupt the normal vaginal flora by killing off beneficial Lactobacillus bacteria, thereby altering the microbiological defense and allowing pathogenic bacteria to proliferate.14

- Hygiene Practices: While the evidence base for some traditional advice is mixed, wiping from back to front after defecation is a plausible mechanism for transferring fecal bacteria directly to the urethral opening and is a risk factor, particularly for children.14

5.3 Comorbid Medical Conditions

- Diabetes Mellitus: Individuals with diabetes are at increased risk for several reasons. High glucose levels in the urine can create a favorable environment for bacterial growth. Furthermore, diabetes can impair the immune system’s ability to fight infection and can cause nerve damage (diabetic neuropathy) that affects bladder control and leads to incomplete emptying.13

- Immunosuppression: Any condition or medication that weakens the immune system—such as HIV, chemotherapy, or long-term corticosteroid use—reduces the body’s capacity to contain an initial bacterial invasion, making progression to a more serious infection more likely.1

- Neurological Conditions: Diseases like multiple sclerosis, Parkinson’s disease, or spinal cord injuries can result in a “neurogenic bladder.” This condition impairs the nerve signals that control bladder function, leading to urinary retention, incontinence, and a high risk of recurrent and complicated UTIs.5

5.4 Healthcare-Associated Factors

- Urinary Catheterization: The presence of an indwelling urinary catheter is the single most important risk factor for developing a UTI in a healthcare setting. Catheter-associated UTIs (CAUTIs) are one of the most common types of healthcare-associated infections.33 The catheter bypasses the body’s primary anatomical defense (the urethra) and provides a direct pathway for bacteria to enter the bladder. The risk of infection increases by 3-7% for each day the catheter remains in place.34

- Urological Instrumentation: Any recent surgery or procedure on the urinary tract, such as cystoscopy or the placement of a ureteral stent, carries a risk of introducing bacteria and causing an infection.4

Section 6: Management and Mitigation: A Proactive Approach to UTIs

While a diagnosed bacterial UTI requires antibiotic therapy for a cure, a range of strategies can be employed to relieve symptoms during an infection and, more importantly, to prevent infections from occurring in the first place.

6.1 Symptom Relief: An Evidence-Based Guide to Home and Over-the-Counter Remedies

It is imperative to state that the following strategies are intended for symptom relief only and are not a substitute for definitive medical treatment. An active bacterial infection, particularly one with upper tract symptoms, requires antibiotics prescribed by a healthcare professional to eradicate the pathogen and prevent progression to pyelonephritis and sepsis.23 Attempting to self-treat a serious infection with home remedies alone is dangerous and risks allowing the infection to escalate.

- Evidence-Based Comfort Measures:

- Hydration: Increasing fluid intake, primarily with water, is a cornerstone of symptom management. It helps dilute the urine, which can reduce the burning sensation during urination, and increases urinary frequency, which aids in mechanically flushing bacteria from the urinary tract.2

- Pain Relievers: Over-the-counter (OTC) analgesics are effective for managing discomfort. Paracetamol (acetaminophen) can reduce pain and fever. Nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs) like ibuprofen can alleviate pain and reduce the inflammation associated with the infection.10

- Heat Application: Applying a warm (not hot) heating pad or hot water bottle to the lower abdomen or back can help soothe the cramping and pelvic pain associated with cystitis.45

- Urinary Anesthetics: In some countries, products containing the active ingredient phenazopyridine are available over-the-counter (e.g., AZO, Pyridium). This drug is a urinary tract-specific analgesic that numbs the lining of the bladder and urethra, providing rapid relief from pain, burning, and urgency. It is important to note that this medication does not treat the infection and will cause the urine to turn a bright orange or red color, which is a normal and harmless side effect.46

- Supplements and Dietary Approaches (Primarily for Prevention):

- The scientific evidence for many popular dietary supplements is focused on their potential role in preventing recurrent UTIs, not in treating an active infection.

- Cranberry Products: Cranberries contain compounds called proanthocyanidins, which are thought to interfere with the ability of E. coli to adhere to the bladder wall. While some studies and reviews suggest that cranberry supplements may be effective in reducing the risk of recurrent UTIs, the evidence is mixed, and they are not effective for treating an established infection.48 Unsweetened cranberry juice or supplements are preferred over sugary juices.

- D-Mannose: This is a type of simple sugar that is structurally similar to the receptors on uroepithelial cells. The theory is that by consuming D-mannose, it will be excreted in the urine and saturate the binding sites on the E. coli fimbriae, preventing them from attaching to the bladder wall. Some clinical studies have shown promise for D-mannose in preventing recurrent UTIs, with some research suggesting it may be as effective as prophylactic antibiotics, but further high-quality research is needed.14

- Probiotics: The use of probiotics, particularly strains of Lactobacillus, aims to restore and maintain a healthy vaginal microbiome. A healthy flora can create an acidic environment that is inhospitable to uropathogens, potentially reducing the risk of colonization and subsequent infection. The evidence for this approach is still emerging.46

- Substances to Avoid During an Active Infection: Certain foods and beverages can irritate the inflamed bladder and worsen symptoms like urgency and pain. These include caffeine, alcohol, spicy foods, acidic fruits, and artificial sweeteners.10 Unproven folk remedies like baking soda or apple cider vinegar lack scientific support and may be harmful.48

| Table 3: An Evidence-Based Review of Non-Antibiotic UTI Management Strategies | |||

| Strategy/Remedy | Proposed Mechanism of Action | Summary of Clinical Evidence | Recommended Use |

| Increased Hydration | Dilutes urine to reduce irritation; increases urination frequency to mechanically flush bacteria.48 | Strong evidence for both symptom relief and prevention of recurrence.51 | Symptom Relief & Prevention |

| OTC Pain Relievers (Ibuprofen, Paracetamol) | Reduce pain, inflammation, and fever.45 | Well-established efficacy for symptomatic relief of pain and fever. | Symptom Relief During Active Infection |

| Phenazopyridine | Acts as a topical analgesic on the urinary tract mucosa.47 | Highly effective for rapid relief of urinary pain, burning, and urgency. Does not treat infection.46 | Symptom Relief During Active Infection |

| Heat Application | Soothes muscle cramping and provides comfort.45 | Common and effective non-pharmacological method for pain relief. | Symptom Relief During Active Infection |

| Cranberry Supplements | Proanthocyanidins may prevent E. coli adhesion to the bladder wall.48 | Evidence for prevention is mixed but growing; no convincing evidence for treating an active infection.51 | Prevention of Recurrence (Potential) |

| D-Mannose | Competitively inhibits E. coli adhesion to the uroepithelium.14 | Emerging evidence suggests it may be effective for prevention, but more high-quality trials are needed.46 | Prevention of Recurrence (Promising) |

| Probiotics (Lactobacillus) | Restore healthy vaginal flora, creating an environment hostile to uropathogens.48 | Some evidence supports use for prevention, particularly in post-menopausal women, but more research is needed.46 | Prevention of Recurrence (Emerging) |

6.2 Foundational Defense: Clinically Supported Prevention Strategies

Preventing a UTI from occurring is the most effective way to avoid its potential complications. The following strategies are supported by clinical evidence and aim to reinforce the body’s natural defenses.

- Maintain Adequate Hydration: Consistently drinking plenty of fluids, primarily water, is a proven strategy for reducing the risk of recurrent UTIs. One study found that increasing daily water intake by 1.5 liters significantly decreased UTI frequency.38

- Proper Toileting and Hygiene:

- After using the toilet, always wipe from front to back. This simple practice helps prevent the transfer of fecal bacteria from the anal region to the urethra.14

- Urinate when the urge arises rather than holding it for long periods. Holding urine allows any bacteria present in the bladder more time to multiply.10

- Make a conscious effort to empty the bladder completely each time you urinate.10

- Sexual Health Practices:

- Urinate shortly after sexual intercourse. This can help to flush out any bacteria that may have been introduced into the urethra during sexual activity.15

- If prone to recurrent UTIs, consider avoiding the use of spermicidal lubricants or diaphragms, as these are known to disrupt the protective vaginal flora.14

- Lifestyle and Personal Care:

- Wear breathable cotton underwear and avoid excessively tight-fitting clothing. This helps to keep the genital area dry and discourages bacterial growth.10

- Opt for showers instead of baths. Sitting in bathwater can potentially introduce bacteria into the urethra.38

- Avoid using potentially irritating feminine products in the genital area, such as douches, deodorant sprays, or scented powders. These can disrupt the natural pH and microbial balance.15

- Targeted Medical Prevention:

- For post-menopausal women with recurrent infections, topical vaginal estrogen therapy (in the form of a cream, tablet, or ring) can be highly effective. It helps to restore a healthier, more acidic vaginal environment and thicker, more resilient tissues, which reduces the risk of infection.46

- In cases of very frequent and debilitating recurrent UTIs, a physician may recommend a course of long-term, low-dose prophylactic antibiotics.51

Section 7: Conclusion: From Awareness to Action

Urinary tract infections exist on a vast spectrum, from a common, easily treated annoyance to a fulminant medical crisis. The analysis presented in this report demonstrates that while the majority of cases remain localized to the lower urinary tract, the potential for a life-threatening progression is real and follows a predictable pathophysiological course. The critical determinant of outcome is the anatomical location of the infection. A UTI confined to the bladder is a local problem; a UTI that ascends to the kidneys becomes a systemic threat.

The single most important takeaway from this comprehensive review is the imperative to recognize the transition from uncomplicated cystitis to the medical emergency of pyelonephritis. The onset of systemic “red flag” symptoms—specifically high fever, shaking chills, flank pain, and nausea or vomiting—must be understood as an alarm bell signaling that the infection has breached local defenses and requires immediate medical intervention. Delay in the face of these symptoms is what allows the cascade to progress to urosepsis, septic shock, and multi-organ failure.

Ultimately, knowledge is the most potent defense against the severe complications of UTIs. A thorough understanding of the key risk factors allows for targeted risk reduction, while adherence to evidence-based prevention strategies can significantly lower the incidence of initial and recurrent infections. By combining proactive prevention with the vigilant recognition of warning signs, the fear of a poorly understood threat can be transformed into an empowered, actionable plan for preserving health and preventing a common ailment from becoming a fatal one.

Works cited

- Urinary tract infections: epidemiology, mechanisms of infection and treatment options – NIH, accessed October 30, 2025, https://pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/articles/PMC4457377/

- Urinary Tract Infections | Johns Hopkins Medicine, accessed October 30, 2025, https://www.hopkinsmedicine.org/health/conditions-and-diseases/urinary-tract-infections

- Urinary Tract Infections – ACCP, accessed October 30, 2025, https://www.accp.com/docs/bookstore/psap/p2018b1_sample.pdf

- Complicated Urinary Tract Infections – StatPearls – NCBI Bookshelf – NIH, accessed October 30, 2025, https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK436013/

- Uncomplicated Urinary Tract Infections – StatPearls – NCBI Bookshelf – NIH, accessed October 30, 2025, https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK470195/

- Urosepsis: Causes, Symptoms, Diagnosis & Treatment – Cleveland Clinic, accessed October 30, 2025, https://my.clevelandclinic.org/health/diseases/25008-urosepsis

- The Dangers of Ignoring a Urinary Tract Infection – Medical Associates of North Texas, accessed October 30, 2025, https://www.mantcare.com/blog/the-dangers-of-ignoring-a-urinary-tract-infection

- Urosepsis – StatPearls – NCBI Bookshelf, accessed October 30, 2025, https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK482344/

- Sepsis – Symptoms & causes – Mayo Clinic, accessed October 30, 2025, https://www.mayoclinic.org/diseases-conditions/sepsis/symptoms-causes/syc-20351214

- Urinary tract infections (UTIs) – NHS, accessed October 30, 2025, https://www.nhs.uk/conditions/urinary-tract-infections-utis/

- my.clevelandclinic.org, accessed October 30, 2025, https://my.clevelandclinic.org/health/diseases/9135-urinary-tract-infections#:~:text=A%20urinary%20tract%20infection%20(UTI)%20is%20an%20infection%20of%20your,Bladder%20(cystitis).

- Urinary Tract Infections | Conditions | UCSF Health, accessed October 30, 2025, https://www.ucsfhealth.org/conditions/urinary-tract-infections

- Urinary tract infections (UTI) – Better Health Channel, accessed October 30, 2025, https://www.betterhealth.vic.gov.au/health/conditionsandtreatments/urinary-tract-infections-uti

- E. Coli and UTIs (Urinary Tract Infections): The Common Connection – Healthline, accessed October 30, 2025, https://www.healthline.com/health/e-coli-uti

- Sepsis from UTI | Understanding the Link for Effective Prevention, accessed October 30, 2025, https://www.endsepsis.org/what-is-sepsis/sepsis-from-uti/

- Kidney infection (Pyelonephritis) symptoms, treatment and prevention, accessed October 30, 2025, https://www.kidneyfund.org/all-about-kidneys/other-kidney-problems/kidney-infection

- Urinary Tract Infections | National Kidney Foundation, accessed October 30, 2025, https://www.kidney.org/kidney-topics/urinary-tract-infections

- Pyelonephritis – Clinical Features – Management – TeachMeSurgery, accessed October 30, 2025, https://teachmesurgery.com/urology/kidney/pyelonephritis/

- Urinary Tract Infections Caused by Uropathogenic Escherichia coli: Mechanisms of Infection and Treatment Options – PMC – NIH, accessed October 30, 2025, https://pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/articles/PMC10341809/

- Acute Pyelonephritis – StatPearls – NCBI Bookshelf, accessed October 30, 2025, https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK519537/

- Comprehensive insights into UTIs: from pathophysiology to precision diagnosis and management – Frontiers, accessed October 30, 2025, https://www.frontiersin.org/journals/cellular-and-infection-microbiology/articles/10.3389/fcimb.2024.1402941/full

- Zoonotic Escherichia coli and urinary tract infections in Southern California | mBio, accessed October 30, 2025, https://journals.asm.org/doi/10.1128/mbio.01428-25

- Nearly 1 in 5 UTIs linked to contaminated meat, claims US study, accessed October 30, 2025, https://timesofindia.indiatimes.com/life-style/health-fitness/health-news/nearly-1-in-5-utis-linked-to-contaminated-meat-claims-us-study/articleshow/124801020.cms

- Urinary Tract Infection(UTI): Symptoms, Diagnosis & Treatment – Urology Care Foundation, accessed October 30, 2025, https://www.urologyhealth.org/urology-a-z/u/urinary-tract-infections-in-adults

- Upper UTI vs. Lower UTI: Symptoms, Diagnosis, and Treatment, accessed October 30, 2025, https://www.healthline.com/health/upper-uti-vs-lower-uti

- Urinary tract infection (UTI) – NHS inform, accessed October 30, 2025, https://www.nhsinform.scot/illnesses-and-conditions/kidneys-bladder-and-prostate/urinary-tract-infection-uti/

- 4 Complications of UTIs Among Older Women – The Urology Group, accessed October 30, 2025, https://www.urologygroup.com/4-complications-of-utis-among-older-women/

- 4 Subtle Signs of a UTI – Women’s Care of Beverly Hills, accessed October 30, 2025, https://www.womenscareofbeverlyhillsgroup.com/post/4-subtle-signs-of-a-uti

- Pyelonephritis – Wikipedia, accessed October 30, 2025, https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Pyelonephritis

- Urinary tract infections in adults | nidirect, accessed October 30, 2025, https://www.nidirect.gov.uk/conditions/urinary-tract-infections-adults

- Kidney infection | NHS inform, accessed October 30, 2025, https://www.nhsinform.scot/illnesses-and-conditions/kidneys-bladder-and-prostate/kidney-infection/

- FAQs: Urinary Tract Infection (UTI) Events | NHSN – CDC, accessed October 30, 2025, https://www.cdc.gov/nhsn/faqs/faq-uti.html

- Catheter-associated Urinary Tract Infection (CAUTI) Basics | UTI – CDC, accessed October 30, 2025, https://www.cdc.gov/uti/about/cauti-basics.html

- Urinary Tract Infection (Catheter-Associated Urinary Tract Infection [CAUTI] and Non-Catheter-Associated Urinary Tract Infection [UTI]) Events – CDC, accessed October 30, 2025, https://www.cdc.gov/nhsn/pdfs/pscmanual/7psccauticurrent.pdf

- Integrated Pathophysiology of Pyelonephritis – ASM Journals, accessed October 30, 2025, https://journals.asm.org/doi/10.1128/microbiolspec.uti-0014-2012

- Urosepsis: Overview of the Diagnostic and Treatment Challenges | Microbiology Spectrum, accessed October 30, 2025, https://journals.asm.org/doi/10.1128/microbiolspec.uti-0003-2012

- Approach to a Patient with Urosepsis – Swan Valley Medical, accessed October 30, 2025, https://swanvalleymedical.com/wp-content/uploads/2022/03/328-Approach-to-a-Patient-with-Urosepsis.pdf

- Urinary Tract Infection Basics – CDC, accessed October 30, 2025, https://www.cdc.gov/uti/about/index.html

- Risk factors and predisposing conditions for urinary tract infection – PMC – PubMed Central, accessed October 30, 2025, https://pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/articles/PMC6502981/

- Recurrent Urinary Tract Infections – StatPearls – NCBI Bookshelf – NIH, accessed October 30, 2025, https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK557479/

- Common Questions About Recurrent Urinary Tract Infections in Women – AAFP, accessed October 30, 2025, https://www.aafp.org/pubs/afp/issues/2016/0401/p560.html

- Recurrent Urinary Tract Infections in Women: Diagnosis and Management – AAFP, accessed October 30, 2025, https://www.aafp.org/pubs/afp/issues/2010/0915/p638.html

- Recurrent uncomplicated urinary tract infections: definitions and risk factors – PMC – NIH, accessed October 30, 2025, https://pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/articles/PMC8167371/

- EAU Guidelines on Urological Infections – Uroweb, accessed October 30, 2025, https://uroweb.org/guidelines/urological-infections/chapter/the-guideline

- How to relieve UTI pain at home fast | Hey Jane, accessed October 30, 2025, https://www.heyjane.com/articles/how-to-relieve-uti-pain-at-home-fast

- 8 UTI Treatments to Try at Home (Antibiotic-Free) – Verywell Health, accessed October 30, 2025, https://www.verywellhealth.com/uti-treatment-at-home-7968150

- OTC UTI Treatment Without Antibiotics- Is it possible? – Family Medicine Austin, accessed October 30, 2025, https://familymedicineaustin.com/otc-uti-treatment-without-antibiotics/

- Overview, Prevention Tips, and Home Remedies for UTIs – Incontinence Institute, accessed October 30, 2025, https://myconfidentlife.com/blog/overview-prevention-tips-and-home-remedies-for-utis

- 7 Home Remedies for Urinary Tract Infections (UTIs) – Health, accessed October 30, 2025, https://www.health.com/condition/sexual-health/uti-home-remedies

- 10 Home Remedies for Kidney Infection: Can I Go … – Healthline, accessed October 30, 2025, https://www.healthline.com/health/kidney-infection-home-remedies

- 9 home remedies for UTIs: How to get rid of bladder infections – Nebraska Medicine, accessed October 30, 2025, https://www.nebraskamed.com/womens-health/gynecology/9-home-remedies-for-utis-how-to-get-rid-of-bladder-infections

- Over the Counter: UTI Treatment – Push Doctor, accessed October 30, 2025, https://www.pushdoctor.co.uk/what-we-treat/sexual-health/urinary-tract-infection-uti/articles/over-the-counter-uti

- Evidence-based review of nonantibiotic urinary tract infection prevention strategies for women: a patient-centered approach – PubMed, accessed October 30, 2025, https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/36862100/

- It’s uncomplicated: Prevention of urinary tract infections in an era of increasing antibiotic resistance – PubMed Central, accessed October 30, 2025, https://pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/articles/PMC10833504/

- It’s uncomplicated: Prevention of urinary tract infections in an era of …, accessed October 30, 2025, https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC10833504/

- Characterizing infection prevention programs and urinary tract infection prevention practices in nursing homes: A mixed-methods study – PMC – NIH, accessed October 30, 2025, https://pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/articles/PMC10782201/

- Diagnosis, Treatment, and Prevention of Urinary Tract Infection | Microbiology Spectrum, accessed October 30, 2025, https://journals.asm.org/doi/10.1128/microbiolspec.uti-0021-2015

Leave Your Comment