Polycystic Ovary Syndrome: Evidence-Based Non-Surgical Management

- August 18, 2025

- 1 Like

- 1465 Views

- 0 Comments

Introduction

Polycystic Ovary Syndrome (PCOS) is a highly prevalent and complex endocrine and metabolic disorder that impacts women of reproductive age globally.1 Affecting an estimated 6–13% of this population, PCOS is often a significant public health concern, with up to 70% of cases potentially remaining undiagnosed worldwide.1 The condition typically begins to manifest in the late teens or early twenties, though its symptoms can appear at any point after the first menstrual period.3 As a leading cause of anovulation and infertility, PCOS poses both immediate reproductive challenges and long-term health risks.1

The syndrome is defined by a constellation of signs and symptoms, although a diagnosis does not require all of them to be present. The most widely accepted criteria for diagnosis, such as the Rotterdam criteria, require the presence of at least two of the following: irregular periods or ovulatory dysfunction, clinical or biochemical hyperandrogenism (excess male hormones), and polycystic ovarian morphology, which is the presence of numerous small, immature follicles on the ovaries.4

This report provides a comprehensive review of the current understanding of PCOS. It delves into the intricate pathophysiological mechanisms that drive the condition, offering a nuanced guide to distinguishing PCOS-related pain from typical menstrual cramps. The analysis extends to a critical evaluation of evidence for a range of non-surgical interventions, including lifestyle modifications, complementary therapies, and a detailed review of pharmacological treatments. The discussion is framed within the context of recent international guidelines and is tailored to an international audience. This paper’s structure follows a logical progression from etiology to symptom-specific and systemic management, providing a holistic view of a condition that significantly impacts physical and emotional well-being across diverse populations.

Pathophysiological Foundations: The Vicious Cycle of PCOS

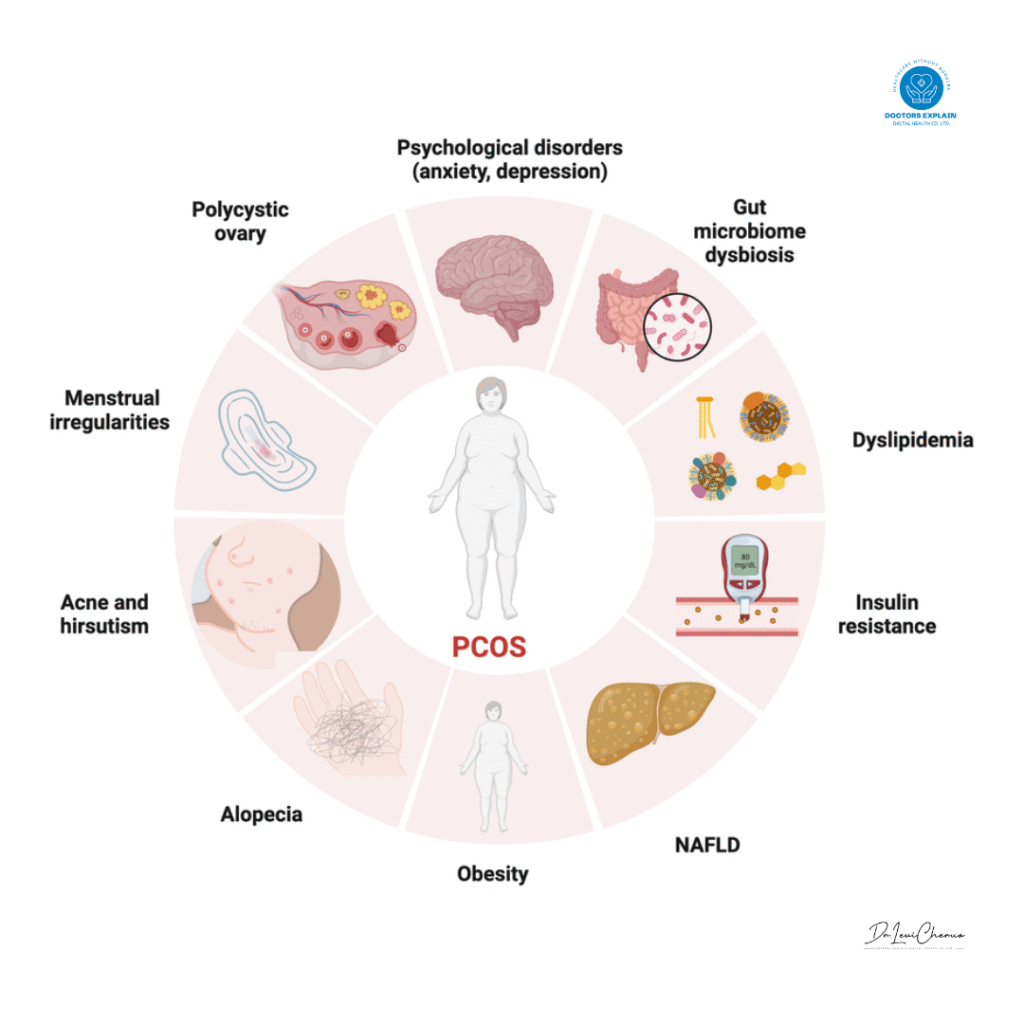

PCOS is not caused by a single, isolated factor but is best understood as a “multi-hit” disorder.8 This model suggests that a combination of genetic predispositions and environmental, metabolic, and hormonal factors creates a complex, self-perpetuating cycle that drives the syndrome’s progression and diverse clinical manifestations. The primary components of this cycle include hyperandrogenism, insulin resistance, and low-grade chronic inflammation, which are intricately linked in a bidirectional feedback loop.

Hyperandrogenism (HA) is a cornerstone of the syndrome, affecting approximately 60–80% of patients.2 It is characterized by an excessive production of male hormones, primarily testosterone, by the ovaries and adrenal glands.4 This hormonal imbalance directly interferes with the regular maturation and release of eggs, a process known as ovulation. As a result, immature follicles accumulate on the ovaries, giving them a “polycystic” appearance on an ultrasound.4 The clinical signs of hyperandrogenism are often the most visible and include hirsutism (excess facial and body hair), severe acne, and male-pattern hair thinning or baldness.4

A significant majority of women with PCOS, an estimated 65–70%, exhibit insulin resistance (IR).12 This is a condition in which the body’s cells become less responsive to the hormone insulin, which is responsible for regulating blood sugar.4 To compensate for this resistance, the pancreas produces more insulin, leading to elevated levels of insulin in the bloodstream, a state known as hyperinsulinemia.4 This hyperinsulinemia is not just a secondary symptom; research suggests it may play a direct causal role in the development and severity of PCOS. One theory posits that hyperinsulinemia can precede the rise in androgen levels, as elevated insulin has been observed in prepubescent daughters of women with PCOS before their testosterone levels increase.8 In addition to its role in glucose metabolism, insulin also acts directly on ovarian thecal cells, stimulating them to produce excess androgens. It can also suppress the liver’s production of Sex Hormone Binding Globulin (SHBG), a protein that binds to testosterone, leading to higher levels of free, biologically active testosterone in the bloodstream.8

The third component of this pathological cycle is a state of low-grade chronic inflammation (SLCI), which is consistently associated with PCOS.12 Unlike acute inflammation, this is a long-term, low-level inflammatory state that may not present with obvious signs but significantly contributes to tissue damage and disease progression.17 This inflammation is deeply intertwined with both insulin resistance and hyperandrogenism. Adipose tissue, particularly in individuals with obesity, acts as an endocrine organ, secreting pro-inflammatory cytokines such as tumor necrosis factor alpha (

TNF−α) and interleukin 6 (IL−6). These substances exacerbate insulin resistance and contribute to the metabolic abnormalities of the syndrome. Furthermore, hyperandrogenism itself can lead to aberrant fat metabolism and adipose tissue dysfunction, further feeding this inflammatory state.9 The complex interplay between these three factors creates a self-reinforcing loop: genetic or environmental factors may trigger initial insulin resistance, which leads to hyperinsulinemia. This in turn stimulates the ovaries to produce excess androgens. This hyperandrogenism then leads to changes in fat metabolism and inflammation, which further worsens insulin resistance, perpetuating the cycle. This complex, multi-systemic model explains the wide array of symptoms and long-term health risks associated with PCOS, including Type 2 diabetes, cardiovascular disease, and metabolic syndrome.10

Differentiating Pain and Manifestations: Beyond “Normal” Cramps

The user query raises a critical and often overlooked question: how to discern whether pelvic pain is a symptom of PCOS rather than just typical menstrual cramps. The relationship between PCOS and pain is complex. While menstrual cramping, or dysmenorrhea, is not a definitive diagnostic criterion for PCOS, it is a common complaint, with one study of women with the condition reporting that 70% experienced severe cramping.19 The key to distinguishing this pain lies not in its fundamental nature but in its context and the presence of other co-occurring symptoms.

The pain associated with PCOS can be categorized as a form of secondary dysmenorrhea, which is menstrual pain caused by an underlying medical condition.19 “Normal” period pain, or primary dysmenorrhea, is a result of uterine contractions that are a natural part of shedding the uterine lining. In women with PCOS, irregular and infrequent periods often mean that the uterine lining builds up over an extended period.19 This can lead to the shedding of a thicker lining, accompanied by higher levels of prostaglandins—chemicals that trigger uterine contractions and pain. This hormonal and inflammatory state amplifies the cramping, making it more severe than what might be considered “normal”.19 In some cases, patients may also experience non-menstrual pelvic pain or belly bloating.20

Given that the pain itself is not a unique sign, the true indicators of PCOS are the constellation of co-occurring, non-cyclic symptoms that are systemic in nature. These “red flags” differentiate PCOS from other causes of pelvic discomfort and signal the need for a comprehensive evaluation. Key distinguishing symptoms include:

- Menstrual Irregularities: Periods that are fewer than nine per year, more than 35 days apart, or unusually long and heavy.4

- Androgen Excess: The onset of new or worsening facial or body hair growth (hirsutism), male-pattern hair loss or thinning on the scalp, and persistent, severe acne.3

- Metabolic Signs: Unexplained weight gain, particularly around the abdomen, and visible skin changes such as dark, velvety patches (acanthosis nigricans) on the neck, armpits, or under the breasts, as well as the appearance of skin tags.10

The failure to recognize this cluster of signs can lead to delayed diagnosis and treatment, as the perception of pain in PCOS patients is often overlooked in clinical settings.9 By understanding that the pain is one piece of a broader, systemic puzzle, individuals can advocate for a proper diagnosis and avoid dismissing their symptoms as merely “normal” period pain. The table below provides a clear reference for distinguishing between PCOS-associated symptoms and common menstrual experiences.

Table 1: Distinguishing Features of PCOS-Associated Symptoms vs. Common Menstrual Experiences

| Symptom Category | Features of Typical Menstrual Experiences | Features Suggestive of PCOS |

| Menstrual Cycle | Regular, predictable cycles (21-35 days). | Irregular, unpredictable, or absent periods; fewer than 9 cycles per year; cycles >35 days apart; prolonged periods lasting many days.4 |

| Pain Characteristics | Occurs during the menstrual period (primary dysmenorrhea); typically subsides within a few days. | Cramping is often severe and may be a form of secondary dysmenorrhea due to hormonal imbalance and inflammation.11 Pelvic pain or bloating may also occur outside of menstruation.20 |

| Androgen Excess | Not associated with excessive hair growth, acne, or hair thinning. | New or worsening hirsutism (facial/body hair), severe acne, male-pattern hair loss.4 |

| Metabolic Indicators | Not associated with weight changes or skin conditions. | Unexplained weight gain (especially around the belly), dark/velvety skin patches (acanthosis nigricans), and skin tags.10 |

| Key Takeaway | Pain is the primary symptom, occurring without other systemic signs. | Pain is part of a larger cluster of symptoms, including menstrual irregularities and signs of androgen excess and insulin resistance.3 |

Non-Pharmacological Interventions: A Foundation of Care

The 2023 international guidelines for PCOS management emphasize that lifestyle modifications are the fundamental first-line therapy for the condition.21 For women who are overweight or obese, even a modest weight reduction of 5% can lead to a significant improvement in symptoms and can restore ovulation, thereby improving menstrual regularity and fertility.21 These changes are crucial for managing the metabolic aspects of PCOS and addressing the core issues of insulin resistance and inflammation.

Dietary Management

The primary objective of dietary intervention is to manage insulin resistance and reduce the state of low-grade inflammation. The recommended approach is not a single, restrictive “PCOS diet” but rather a well-balanced, low-glycemic, and anti-inflammatory eating plan, such as the Mediterranean diet.24 This strategy focuses on stabilizing blood sugar levels and avoiding the sharp insulin spikes that can exacerbate hyperandrogenism.

To achieve these goals, individuals are advised to limit or avoid foods that can cause inflammation and insulin surges. These include refined carbohydrates (such as white bread, pasta, and sugary breakfast cereals), sugary beverages, processed meats, saturated fats, and fried foods.24 The focus should shift toward whole, unprocessed options that are rich in fiber and lean protein. Recommended foods include whole grains, leafy greens and other non-starchy vegetables, lean protein sources like fish and chicken, legumes, and fruits.24 Omega-3 rich fish, such as salmon and sardines, are particularly beneficial for their anti-inflammatory properties.25

Physical Activity

Regular physical activity is another critical component of lifestyle management. Exercise helps to lower blood sugar levels and can directly improve insulin sensitivity. The general recommendation for the prevention of weight gain is at least 150 minutes of moderate-intensity exercise per week.21 This commitment to daily physical movement, in combination with a low-glycemic diet, can help regulate weight and may even restore ovulation.23

Complementary and Herbal Supplements

The use of nutritional supplements and herbs for PCOS management is gaining attention, but the scientific evidence for their efficacy varies. A detailed, evidence-based assessment is necessary to distinguish between promising treatments and those with limited data.

- Inositol: This supplement, a form of sugar naturally found in the body, is a promising insulin-sensitizing agent and is considered a viable adjunct to lifestyle and medical therapy.14 Clinical trials and meta-analyses suggest that supplementation with myo-inositol (MYO) can improve ovulation frequency, reduce testosterone concentrations, and improve metabolic markers in women with PCOS.14 The optimal therapeutic ratio of MYO to D-chiro-inositol (DCI) appears to be at least 40:1, as research indicates that high doses of DCI alone may not be effective and could even worsen outcomes.27

- N-acetylcysteine (NAC): As a derivative of the amino acid cysteine, NAC has antioxidant properties that may improve insulin receptor activity.28 Studies indicate that NAC can improve ovulation and pregnancy rates in women with PCOS who are resistant to the fertility drug clomiphene.26 It has also demonstrated efficacy in improving metabolic parameters and reducing testosterone levels, making it a potential alternative to metformin for some individuals.15

- Spearmint Tea: Research has shown that drinking two cups of spearmint tea daily can have significant anti-androgenic effects.26 A randomized controlled trial demonstrated a reduction in free and total testosterone levels in women with PCOS after just 30 days of consumption. While this hormonal shift was associated with a self-reported improvement in hirsutism, objective measures did not show a significant reduction, likely due to the short duration of the study.29 This suggests that while spearmint tea has a clear anti-androgen effect, patience and long-term use are required for visible clinical improvement.

- Other Supplements: The evidence for other supplements like cinnamon, chromium, and turmeric is promising but still requires more robust, large-scale studies.26 For example, while some studies on turmeric show beneficial effects on ovulation, others suggest it may improve body weight and glycemic control.31 Similarly, cinnamon has shown some promise in improving insulin sensitivity in small studies.26 These options should be considered as complementary therapies rather than stand-alone treatments.

The following table provides a summary of the evidence for key nutritional and supplemental interventions.

Table 2: Summary of Evidence for Key Nutritional, Herbal, and Supplemental Interventions for PCOS

| Intervention | Primary Symptom Target | Level of Evidence | Efficacy & Note |

| Diet (Mediterranean/Low-Glycemic) | Insulin resistance, weight management, inflammation | Clinical consensus, multiple studies | First-line therapy. Reduces insulin spikes, improves metabolic health, and aids weight loss, which can normalize menstrual cycles.24 |

| Physical Activity | Insulin resistance, weight management | Clinical consensus, multiple studies | First-line therapy. Improves insulin sensitivity and helps maintain a healthy weight, which can alleviate symptoms.21 |

| Inositol (MYO + DCI) | Ovulation, insulin resistance, hyperandrogenism | Meta-analyses, randomized controlled trials (RCTs) | Improves ovulation frequency, reduces testosterone, and improves metabolic profile. The 40:1 ratio is most effective; high doses of DCI alone are not recommended.14 |

| N-acetylcysteine (NAC) | Ovulation, insulin resistance, hyperandrogenism | Meta-analyses, RCTs | Improves ovulation and pregnancy rates, particularly in clomiphene-resistant women. May also reduce testosterone levels and improve metabolic markers.15 |

| Spearmint Tea | Hirsutism, hyperandrogenism | Small RCTs | Reduces free and total testosterone levels and improves patient-reported hirsutism. Longer-term studies are needed for objective clinical proof.26 |

| Cinnamon | Insulin resistance | Small placebo-controlled study | Appears to improve insulin sensitivity, but more research is needed to confirm efficacy.26 |

Non-Surgical Medical Interventions: A Multimodal Approach

For many women with PCOS, non-surgical medical interventions are necessary to manage symptoms that do not adequately respond to lifestyle changes alone. The selection of the most effective treatment is highly personalized and depends on the patient’s dominant symptoms, whether they wish to become pregnant, and their overall health profile. The most effective approach is often a multimodal one, where different medications are used to target distinct aspects of the syndrome.

Hormonal Therapies for Cycle and Symptom Management

Combined Oral Contraceptives (COCs) are a common and effective first-line treatment for women who do not wish to conceive.23 These pills, which contain both estrogen and progestin, work to regulate menstrual cycles by decreasing androgen production and regulating estrogen levels.23 This hormonal regulation not only corrects irregular bleeding but also significantly improves androgen-related symptoms such as acne and hirsutism.23 Furthermore, using COCs provides crucial protection against the risk of endometrial cancer, which is elevated in women with PCOS due to the long-term, irregular thickening of the uterine lining.5 Common side effects, such as spotting, nausea, and headaches, often resolve within the first two to three months of use.33

For women who cannot take estrogen, progestin therapy (e.g., a progestin-only mini-pill, shot, or IUD) can be used to regulate periods and protect against endometrial cancer. However, this therapy does not improve the androgen-related symptoms of acne and excessive hair growth.23

Insulin-Sensitizing Agents: The Role of Metformin

Metformin, a medication commonly used to treat Type 2 diabetes, is a first-line therapy for the metabolic aspects of PCOS.35 Its mechanism of action involves decreasing the production of glucose in the liver and improving the body’s sensitivity to insulin.36 By reducing hyperinsulinemia, metformin can lead to a decrease in androgen levels, which may help to regulate menstrual patterns.35 The medication may also aid in weight management, although its effects on weight loss are often modest and are more related to a reduced appetite than direct metabolic changes.38 While metformin can improve ovulation and menstrual regularity, it is generally considered less effective than specific ovulation induction drugs like clomiphene or letrozole at achieving a live birth.39 A key consideration for patients is the high incidence of gastrointestinal side effects, such as upset stomach, gas, and bloating, which are common and often dose-dependent.35

Anti-Androgens for Cosmetic Symptoms

For women whose primary concern is the physical manifestation of hyperandrogenism, medications that directly block androgen activity can be effective. Spironolactone is a common choice for treating hirsutism and acne.40 It works by blocking the effects of androgens at the level of the skin and hair follicles.41 While it can significantly improve these symptoms, it does not typically help with androgen-related hair loss from the scalp.40 Spironolactone is often used in combination with COCs. A major caution is its teratogenic potential, meaning it can cause birth defects, and therefore requires the use of effective contraception for any sexually active patient.23 Another option is the prescription topical cream

eflornithine (Vaniqa), which can be applied directly to the face to slow hair growth.23

Ovulation Induction for Infertility

For women with PCOS who are experiencing infertility due to anovulation, a variety of medications can be used to induce ovulation. The 2023 international guidelines now recommend Letrozole (Femara) as the first-line oral medication for this purpose.39 Letrozole is an aromatase inhibitor that temporarily lowers estrogen levels, which in turn prompts the pituitary gland to secrete more Follicle-Stimulating Hormone (FSH), stimulating the ovaries to produce a lead follicle and induce ovulation.39 Research has shown that Letrozole has a higher ovulation rate and live birth rate compared to the older first-line medication,

Clomiphene (Clomid).39 Clomiphene, a Selective Estrogen Receptor Modulator (SERM), can also induce ovulation but carries a higher risk of multiple pregnancies and can sometimes thin the uterine lining, which may interfere with implantation.39

Gonadotropins, which are injectable hormone medications, and In Vitro Fertilization (IVF) are typically reserved for patients who do not respond to oral medications.39

The following table provides a clear comparison of key non-surgical medical interventions.

Table 3: Comparison of Key Non-Surgical Interventions by Symptom Target, Efficacy, and Side Effect Profile

| Intervention | Primary Symptom Target | Efficacy | Side Effects & Considerations |

| Combined Oral Contraceptives (COCs) | Irregular periods, hyperandrogenism (acne, hirsutism), endometrial protection | Regulates periods and reduces androgen levels. A primary treatment for symptom management.23 | Common side effects (headaches, nausea, spotting) often resolve. Protects against endometrial cancer.23 |

| Metformin | Insulin resistance, metabolic syndrome, menstrual irregularity | Highly effective for metabolic symptoms and lowering insulin/androgen levels. Less effective for hirsutism than COCs or anti-androgens.32 | Common gastrointestinal upset (nausea, gas, bloating).35 |

| Spironolactone | Hirsutism, acne | Effective at blocking androgen effects on skin and hair follicles.40 | Teratogenic (causes birth defects). Requires effective contraception for sexually active patients. Less effective for scalp hair loss.23 |

| Letrozole (Femara) | Ovulation induction for infertility | Considered first-line for ovulation induction. Research shows higher ovulation and live birth rates than Clomiphene with a lower twin risk.39 | Hot flashes.39 |

| Clomiphene (Clomid) | Ovulation induction for infertility | An older but still used option. Effective for inducing ovulation.39 | Higher risk of twin pregnancies than Letrozole; may thin the uterine lining.39 |

Conclusion and Future Directions

Polycystic Ovary Syndrome is a chronic, multi-systemic condition with a complex etiology rooted in a vicious cycle of hyperandrogenism, insulin resistance, and low-grade inflammation. The report demonstrates that effective symptom differentiation requires a holistic approach, moving beyond a single symptom like pelvic pain to identify a cluster of co-occurring signs that signal the underlying condition.

The most effective management strategies are multimodal and highly individualized. They are grounded in a foundation of lifestyle modifications, including a low-glycemic, anti-inflammatory diet and regular physical activity, which address the core metabolic and inflammatory drivers of the syndrome. These non-pharmacological approaches may be complemented by nutritional supplements like inositol and N-acetylcysteine, which have demonstrated promising results in clinical trials. Pharmacological interventions are selected based on the patient’s dominant symptoms and life goals, whether it is to regulate periods and manage cosmetic symptoms with hormonal birth control and anti-androgens, or to restore fertility with ovulation induction agents.

The 2023 International Evidence-based Guideline for the assessment and management of PCOS represents a significant step forward in standardizing care. It offers a refined diagnostic algorithm that now includes anti-Müllerian hormone (AMH) testing as an alternative to ultrasound in adults and a stronger emphasis on a holistic, patient-centered approach that considers mental health and quality of life.43

Despite this progress, key gaps in the scientific literature remain. There is a need for more high-quality, long-term randomized controlled trials to fully elucidate the efficacy and safety of many interventions, particularly supplements.28 Further research is also needed to better understand the subjective experience of chronic pain and its impact on the quality of life of those with PCOS, as this is an area that is often neglected in clinical settings.9

PCOS is a manageable condition, but it requires a lifelong commitment to a personalized plan of care. By empowering individuals with a deeper understanding of the condition and fostering shared decision-making with healthcare providers, it is possible to significantly improve both short-term symptoms and long-term health outcomes on a global scale.

Works cited

- Polycystic ovary syndrome – World Health Organization (WHO), accessed August 18, 2025, https://www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/polycystic-ovary-syndrome

- Global burden of polycystic ovary syndrome among women of childbearing age, 1990–2021, accessed August 18, 2025, https://www.frontiersin.org/journals/public-health/articles/10.3389/fpubh.2025.1514250/full

- Polycystic ovary syndrome – Symptoms – NHS, accessed August 18, 2025, https://www.nhs.uk/conditions/polycystic-ovary-syndrome-pcos/symptoms/

- Polycystic ovary syndrome (PCOS) – Symptoms and causes – Mayo Clinic, accessed August 18, 2025, https://www.mayoclinic.org/diseases-conditions/pcos/symptoms-causes/syc-20353439

- Diagnosing Polycystic Ovary Syndrome – NYU Langone Health, accessed August 18, 2025, https://nyulangone.org/conditions/polycystic-ovary-syndrome/diagnosis

- Polycystic ovary syndrome (PCOS) – Better Health Channel, accessed August 18, 2025, https://www.betterhealth.vic.gov.au/health/conditionsandtreatments/polycystic-ovarian-syndrome-pcos

- Diagnosis and management of polycystic ovarian syndrome – CMAJ, accessed August 18, 2025, https://www.cmaj.ca/content/196/3/E85

- Insulin and Androgens in Polycystic Ovary Syndrome: Which Is the Causal Factor?, accessed August 18, 2025, https://www.medcentral.com/endocrinology/hormones/insulin-and-androgens-in-polycystic-ovary-syndrome-which-is-the-causal

- Evaluation of Bodily Pain Associated with Polycystic Ovary Syndrome: A Review of Health-Related Quality of Life and Potential Risk Factors – PubMed Central, accessed August 18, 2025, https://pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/articles/PMC9776021/

- Mayo Clinic Health Library – Polycystic ovary syndrome (PCOS) – Swiss Medical Network, accessed August 18, 2025, https://www.swissmedical.net/en/healtcare-library/con-20314571

- 10 Symptoms of Polycystic Ovary Syndrome (PCOS) – The University of Kansas Health System, accessed August 18, 2025, https://www.kansashealthsystem.com/news-room/blog/2019/05/pcos-symptoms

- The Role of Polycystic Ovary Syndrome in Reproductive and Metabolic Health: Overview and Approaches for Treatment, accessed August 18, 2025, https://diabetesjournals.org/spectrum/article/28/2/116/32616/The-Role-of-Polycystic-Ovary-Syndrome-in

- Insulin Resistance in Polycystic Ovary Syndrome: Progress and Paradoxes – Endocrine Society, accessed August 18, 2025, https://www.endocrine.org/~/media/endosociety/files/ep/rphr/56/rphr_vol_56_ch_14_insulin_resistance_in_polycystic_ovary.pdf

- Myo-inositol effects in women with PCOS: a meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials in, accessed August 18, 2025, https://ec.bioscientifica.com/view/journals/ec/6/8/EC-17-0243.xml

- The effects of N-acetylcysteine supplement on metabolic parameters in women with polycystic ovary syndrome: a systematic review and meta-analysis – Frontiers, accessed August 18, 2025, https://www.frontiersin.org/journals/nutrition/articles/10.3389/fnut.2023.1209614/full

- Systematic low-grade chronic inflammation and intrinsic mechanisms in polycystic ovary syndrome – Frontiers, accessed August 18, 2025, https://www.frontiersin.org/journals/immunology/articles/10.3389/fimmu.2024.1470283/full

- Chronic low-grade inflammation and ovarian dysfunction in women with polycystic ovarian syndrome, endometriosis, and aging – Frontiers, accessed August 18, 2025, https://www.frontiersin.org/journals/endocrinology/articles/10.3389/fendo.2023.1324429/full

- Controversies in the Pathogenesis, Diagnosis and Treatment of PCOS: Focus on Insulin Resistance, Inflammation, and Hyperandrogenism – MDPI, accessed August 18, 2025, https://www.mdpi.com/1422-0067/23/8/4110

- Does PCOS Cause Cramps? – HealthMatch, accessed August 18, 2025, https://healthmatch.io/pcos/pcos-cramps

- Polycystic Ovary Syndrome (PCOS) – Johns Hopkins Medicine, accessed August 18, 2025, https://www.hopkinsmedicine.org/health/conditions-and-diseases/polycystic-ovary-syndrome-pcos

- Polycystic ovary syndrome – Wikipedia, accessed August 18, 2025, https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Polycystic_ovary_syndrome

- Treatment : Polycystic ovary syndrome – NHS, accessed August 18, 2025, https://www.nhs.uk/conditions/polycystic-ovary-syndrome-pcos/treatment/

- Polycystic ovary syndrome (PCOS) – Diagnosis and treatment – Mayo Clinic, accessed August 18, 2025, https://www.mayoclinic.org/diseases-conditions/pcos/diagnosis-treatment/drc-20353443

- PCOS Diet | Johns Hopkins Medicine, accessed August 18, 2025, https://www.hopkinsmedicine.org/health/wellness-and-prevention/pcos-diet

- PCOS Diet: Foods to Eat and Avoid – Healthline, accessed August 18, 2025, https://www.healthline.com/health/pcos-diet

- Natural treatments for polycystic ovary syndrome | EBSCO Research Starters, accessed August 18, 2025, https://www.ebsco.com/research-starters/complementary-and-alternative-medicine/natural-treatments-polycystic-ovary

- Full article: Update on the combination of myo-inositol/d-chiro-inositol for the treatment of polycystic ovary syndrome – Taylor & Francis Online, accessed August 18, 2025, https://www.tandfonline.com/doi/full/10.1080/09513590.2023.2301554

- N-Acetylcysteine for Polycystic Ovary Syndrome: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis of Randomized Controlled Clinical Trials – PMC – PubMed Central, accessed August 18, 2025, https://pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/articles/PMC4306416/

- Spearmint herbal tea has significant anti-androgen effects in polycystic ovarian syndrome. A randomized controlled trial – PubMed, accessed August 18, 2025, https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/19585478/

- Spearmint and Facial Hair: What Studies Say – Oana – Posts, accessed August 18, 2025, https://www.oanahealth.com/post/spearmint-and-facial-hair-what-studies-say

- Spices And Herbs for PCOS: Natural PCOS Treatment – Allara Health, accessed August 18, 2025, https://www.allarahealth.com/spices-and-herbs-for-pcos-natural-pcos-treatment

- PCOS Treatments – PCOS Awareness Association, accessed August 18, 2025, https://www.pcosaa.org/pcos-treatments

- What are the side effects of the birth control pill? – Planned Parenthood, accessed August 18, 2025, https://www.plannedparenthood.org/learn/birth-control/birth-control-pill/birth-control-pill-side-effects

- gremjournal.com, accessed August 18, 2025, https://gremjournal.com/journal/the-hormonal-contraceptive-choice-in-women-with-polycystic-ovary-syndrome-and-metabolic-syndrome/#:~:text=Progestin%20only%20contraceptives%20in%20PCOS%20women&text=Over%20time%2C%20these%20contraceptives%20can,cause%20spotting%20or%20breakthrough%20bleeding.

- Metformin vs Birth Control for PCOS – Oana – Posts, accessed August 18, 2025, https://www.oanahealth.com/post/metformin-vs-birth-control-for-pcos/?utm_source=chatgpt.com

- Metformin-Clinical Pharmacology in PCOs – PMC – PubMed Central, accessed August 18, 2025, https://pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/articles/PMC4392089/

- (PDF) Metformin-Clinical Pharmacology in PCOs – ResearchGate, accessed August 18, 2025, https://www.researchgate.net/publication/274900952_Metformin-Clinical_Pharmacology_in_PCOs

- Metformin for Polycystic Ovary Syndrome – Children’s Hospital Colorado, accessed August 18, 2025, https://www.childrenscolorado.org/globalassets/departments/gynecology/informational-pdfs/options-for-managing-pcos-metformin.pdf?v=490a43

- Inducing Ovulation in PCOS | RMANY Blog – Reproductive Medicine Associates of New York, accessed August 18, 2025, https://www.rmany.com/blog/inducing-ovulation-in-pcos-dr-kimberley-thornton

- Treatment – PCOS Awareness Association, accessed August 18, 2025, https://www.pcosaa.org/treatment

- Spironolactone for PCOS | How It Works and Safety – XYON, accessed August 18, 2025, https://xyonhealth.com/blogs/library/spironolactone-for-pcos

- PCOS (Polycystic Ovary Syndrome): Symptoms & Treatment – Cleveland Clinic, accessed August 18, 2025, https://my.clevelandclinic.org/health/diseases/8316-polycystic-ovary-syndrome-pcos

- Summary of the 2023 international evidence-based guideline for the assessment and management of polycystic ovary syndrome: an Australian perspective – PubMed, accessed August 18, 2025, https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/39223729/

- The 2023 guidelines for diagnosing PCOS: What OB-GYNs need to know – LEVY Health, accessed August 18, 2025, https://levy.health/2023-guidelines-for-diagnosing-pcos-2/

- Polycystic Ovary Syndrome: Assessment and Management Guidelines – AAFP, accessed August 18, 2025, https://www.aafp.org/pubs/afp/issues/2024/1100/practice-guidelines-polycystic-ovary-syndrome.html

- Efficacy and safety of metformin or oral contraceptives, or both in polycystic ovary syndrome, accessed August 18, 2025, https://pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/articles/PMC4562722/

Leave Your Comment