How to Help a Loved One During an Asthma Attack Without an Inhaler

- June 11, 2025

- 1 Like

- 726 Views

- 0 Comments

Abstract

Asthma is a chronic respiratory condition affecting more than 262 million people worldwide and responsible for over 455,000 deaths annually (World Health Organization [WHO], 2023). While access to medications like short-acting beta-agonist (SABA) inhalers can manage most attacks, emergency situations often arise where patients do not have their inhalers readily available. This paper investigates non-pharmacological interventions for managing acute asthma attacks at home in the absence of inhalers. It synthesizes evidence-based guidance from reputable medical organizations, peer-reviewed studies, and expert recommendations, and provides globally applicable, practical solutions for caregivers. The study also considers the role of poverty, geographical access, and emergency preparedness in asthma management. The findings underline the critical importance of community health education, preventive care, and system-level interventions in improving outcomes in asthma-related emergencies.

Introduction

Imagine your child, sibling, or spouse gasping for air, eyes wide with fear, chest heaving. You frantically search the drawers, under the couch, and in every pocket, only to realize—the inhaler is nowhere to be found. In many households across the globe, particularly in low-resource settings, this scenario is a terrifying reality.

Asthma affects approximately 1 in 13 people globally (Centers for Disease Control and Prevention [CDC], 2023). In emergencies, access to a quick-relief inhaler is often the difference between life and death. Yet, what happens when a loved one experiences an asthmatic attack and there’s no inhaler in sight? This question is not just theoretical. For millions, it’s an everyday risk due to poverty, drug stock-outs, or misplaced medication.

This paper aims to offer practical, medically sound guidance for non-medical caregivers in such emergencies, while addressing global disparities in asthma care. The paper explores techniques grounded in physiology, outlines what not to do, and offers an overview of systemic gaps that make such emergencies more common in some parts of the world.

Understanding Asthma and Acute Asthmatic Attacks

Asthma is a chronic inflammatory disease of the airways that leads to periodic episodes of bronchoconstriction, airway inflammation, and increased mucus production (Global Initiative for Asthma [GINA], 2023). During an asthma attack—also called an exacerbation—the muscles around the airways tighten (bronchospasm), and the airway lining becomes swollen or inflamed, narrowing the breathing passage.

Symptoms of an acute attack include:

- Shortness of breath

- Wheezing

- Chest tightness

- Coughing

- Cyanosis (bluish lips or nails)

- Difficulty speaking in full sentences

In severe cases, without rapid intervention, asthma attacks can lead to respiratory failure or death.

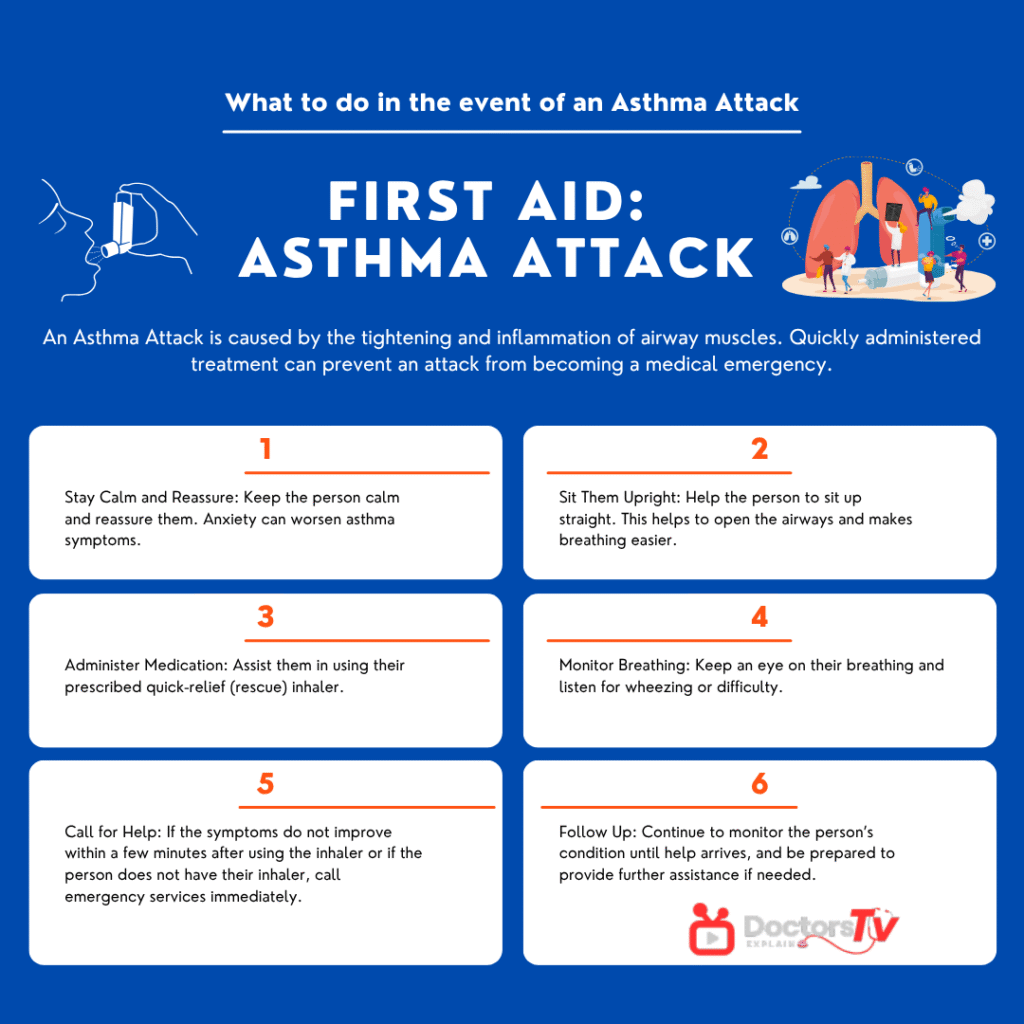

First Response: Stay Calm and Reassure the Person

The first step is deceptively simple: stay calm. Asthma symptoms worsen with anxiety due to hyperventilation and increased airway reactivity (Schatz et al., 2019). Speak in a calm, reassuring voice and encourage the person to sit upright rather than lie down. This posture helps expand the lungs and allows for better diaphragmatic breathing (British Thoracic Society, 2019).

Step-by-Step Emergency Interventions Without an Inhaler

1. Positioning: The Tripod Pose

Encourage the person to sit in a tripod position—leaning forward with hands on the knees. This position optimizes accessory muscle use and reduces work of breathing (O’Driscoll et al., 2021).

✅ DO: Sit upright, lean slightly forward.

❌ DON’T: Lie the person flat on their back.

2. Pursed-Lip Breathing

This breathing technique slows exhalation, prevents airway collapse, and improves oxygenation. Teach the person to:

- Inhale slowly through the nose for 2 seconds.

- Exhale gently through pursed lips for 4 seconds.

Studies have shown that pursed-lip breathing improves oxygen saturation and reduces dyspnea in patients with obstructive lung diseases (Yancosek et al., 2020). Though primarily studied in COPD, the physiological mechanism benefits asthma too.

3. Eliminate Environmental Triggers

Quickly assess and remove any possible asthma triggers:

- Smoke, dust, pet dander

- Strong scents like perfumes, cleaning sprays

- Cold air—close windows or relocate if outdoors

“He who is bitten by a snake fears a lizard.” – African proverb. Once an asthma trigger is known, even similar substances can set off fear—or an attack.

4. Steam and Warm Fluids (Cautiously)

Inhalation of warm, humid air may help loosen mucus in mild cases. However, this is not a substitute for medication.

- Use a bowl of hot water with a towel over the head (carefully, to avoid burns).

- Warm, non-caffeinated fluids like tea or broth can help soothe airways.

Caution: Steam therapy is controversial. For some, it may worsen symptoms, especially if the asthma is triggered by humidity or heat (National Health Service [NHS], 2022).

5. Use of Caffeine as a Bronchodilator (with Limits)

Caffeine is chemically similar to theophylline, a bronchodilator once commonly used in asthma. A 2010 Cochrane review found that caffeine can modestly improve airway function for up to four hours (Welsh et al., 2010). A strong cup of black coffee or tea might offer temporary relief.

Reference:

Welsh, E. J., Bara, A., Barrow, I., & Cates, C. J. (2010). Caffeine for asthma. Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews, (1), CD001112. https://doi.org/10.1002/14651858.CD001112.pub2

When to Call Emergency Services

Always err on the side of caution. If the person:

- Struggles to speak

- Shows signs of cyanosis

- Has a silent chest (no wheeze)

- Is becoming confused or drowsy

Call emergency services immediately.

Myth-Busting: Dangerous Home Remedies to Avoid

❌ Essential oils: Can worsen bronchospasm.

❌ Honey or sugar water: Not helpful in acute settings.

❌ Holding breath or rapid deep breathing: Can cause hyperventilation.

Broader Context: Why Are Inhalers Often Missing?

In many regions, particularly in Africa, Latin America, and parts of Asia, access to asthma medication is a luxury. A 2019 study by the Global Asthma Network found that short-acting inhalers were unavailable in over 50% of public health facilities in low-income countries (The Union, 2019).

“Poverty is a disease without a cure, but not without treatment.” – African proverb.

Cost and access remain massive barriers. In Kenya, for example, a salbutamol inhaler may cost more than a day’s wage in informal settlements (Ong’ayo et al., 2021).

Long-Term Strategies: Prevention and Preparedness

- Education: Teach every family member asthma first aid.

- Duplicate Inhalers: Keep extra inhalers in key locations.

- Asthma Action Plan: A written guide from a healthcare provider.

- Mobile Health Tools: Apps like AsthmaMD or Propeller Health help track symptoms and medication use.

Conclusion

Asthma emergencies at home without an inhaler are frightening but manageable if the caregiver is prepared. Through proper positioning, breathing techniques, environmental control, and use of everyday items like coffee, lives can be saved. However, these measures are stopgaps—not substitutes for professional care. The international health community must prioritize access, affordability, and education to reduce preventable asthma deaths.

References

British Thoracic Society. (2019). Guidelines for the management of asthma. https://www.brit-thoracic.org.uk/quality-improvement/guidelines/asthma/

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. (2023). Asthma data, statistics, and surveillance. https://www.cdc.gov/asthma/asthmadata.htm

Global Initiative for Asthma (GINA). (2023). Global strategy for asthma management and prevention. https://ginasthma.org/

National Health Service (NHS). (2022). Asthma: Symptoms and treatments. https://www.nhs.uk/conditions/asthma/

O’Driscoll, B. R., Howard, L. S., Earis, J., & Mak, V. (2021). BTS guideline for oxygen use in adults. Thorax, 72(Suppl 1), ii1-ii90. https://doi.org/10.1136/thoraxjnl-2021-216163

Schatz, M., Zeiger, R. S., & Vollmer, W. M. (2019). Asthma exacerbation: The role of anxiety. Annals of Allergy, Asthma & Immunology, 123(3), 245–252. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.anai.2019.07.006

The Union. (2019). Asthma care in low-resource settings: Access and affordability. https://theunion.org/news/access-to-inhalers-in-low-income-countries

Welsh, E. J., Bara, A., Barrow, I., & Cates, C. J. (2010). Caffeine for asthma. Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews, (1), CD001112. https://doi.org/10.1002/14651858.CD001112.pub2

World Health Organization. (2023). Asthma. https://www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/asthma

Yancosek, K. E., Howell, D. M., & Kristman-Valente, A. (2020). Pursed-lip breathing technique for management of dyspnea. Journal of CardioPulmonary Rehabilitation, 40(1), 35–40. https://doi.org/10.1097/HCR.0000000000000450

Leave Your Comment